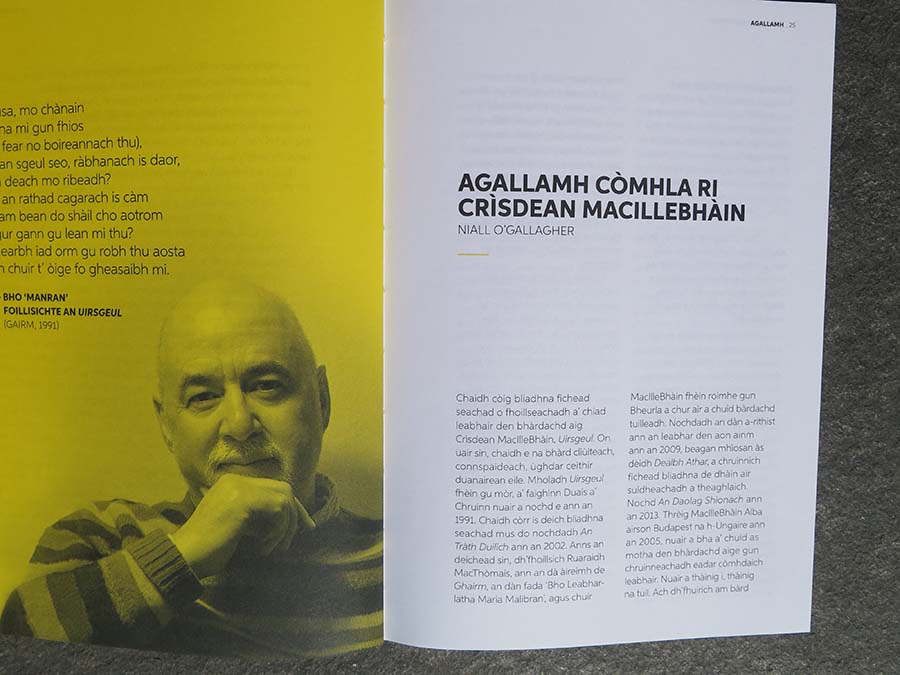

An interview with Niall O’Gallagher for Steall magazine

NO’G We learn from the book itself that the poems in Uirsgeul / Myth were written in the course of only 2 years, in Edinburgh and in Italy. Could you tell me something about that period?

CMacIB I came back from Italy, where I had spent 10 years, in 1985. After a year working on my Ph.D. in Glasgow, I started teaching in the Department of English Literature in the University of Edinburgh. I wrote the first poems in the book, the sequence ‘The Scholar Looks Back’, in spring 1987. My Italian partner, Giuseppe, was staying with me at the time. The weather was exceptionally warm and sunny and we explored Edinburgh together, taking long walks in each area of the city. One afternoon we attended a concert at the Danish Institute. A string quartet was playing the music of Carl Nielsen. The idea of the sequence came to me while I was listening. I made notes on the concert programme and then, back home, in the days that followed, I wrote the poems. When they were published in Gairm, Michel Byrne and Meg Bateman came to visit me and heard me read the poems. For a couple of years, Meg and I would show each other the latest things we had written. It was a way of supporting and encouraging each other.

I regularly returned to Italy. Giuseppe and I spent summer 1988 in Cortona, where I wrote ‘Rex Tenebrarum’, a very significant piece in my opinion, which explains how I perceived good in what was supposedly evil, and evil in the things I had been taught were good. It was in part inspired by the opening of the third of Rilke’s Duino Elegies. I also see in it the influence of an essay by Tsvetaeva which I read in Italian translation, where she discusses her fascination with the image of the Devil when she was a little girl. I made trips to Croatia, as can be seen in the poem ‘Lipe zelene livade’. The poem ‘In Ljubljana’ addresses the Slovenia poet Tomaž Šalamun. He and I met for the first time in May 1986.

NO’G So was evil among the elements that set you writing poetry, or at any rate a poem dealing with that? In ‘Rex Tenebrarum’ you wrote that ‘life and nourishment come from darkness’. Can you explain the meaning of this riddle?

CMacIB I am not able to say precisely what evil is. There are times when I believe it accompanies us in a specific form, like an active person. I think of Achmatova’s lines: ‘evil roaming/ through the world with on its shoulders/ nothing but a knapsack…’ At other times, I believe evil is nothing more than the absence of something positive and beautiful – as cold is merely the absence of heat.

‘Rex Tenebrarum’ isn’t a poem about evil. It’s an attack on erroneous doctrine, which in the process uncovers a new morality and new principles. I have never seen darkness as something bad, while light would be something good. Things aren’t that simple. We need darkness if we are going to sleep, and each of us spends nine months in the darkness of our mother’s womb before entering the world. Nothing bad about a place like that!

NO’G One poem, addressing the language itself, says: ‘They told me that you were old, but your youth enchanted me’. That contradicts the usual image of Gaelic. What made Gaelic young? And how did it enchant you?

CMacIB I began writing poetry relatively late. I was 35 years old – no way to claim that I was young at the time! From when I was a boy, I had experienced English as an alien tongue that didn’t really belong to me. When I went to study at Cambridge, age 18, that impression grew stronger. English culture was far-reaching and highly developed, but for me it was neither efficacious nor productive. When I started writing in Gaelic, the language gave me the chance to deal with a range of topics I had been incapable of opening up or exploring before then. That was why I looked on Gaelic as a fresh start, a key to places within me, also places with general relevance, which till then had been cut off and forbidden.

NO’G At many points the poems say that something stopped you from speaking, that speech was not permitted, even sinful. Can you say why? And was the solution you found in this book a permanent one?

CMacIB I don’t think you can find permanent solutions to blockages of that sort. Anyone who writes poetry, anyone who creates, needs over and over again to come up with a way to begin afresh, to carry on working steadily and resolutely. Looking back, I get the impression I was an impossible subject, speaking and writing out of an impossible position. I was gay in a country that, in the years when I grew up, was utterly hostile and intolerant; a Catholic at a time when Catholics in Scotland were the objects of shameful prejudice and discrimination; Scottish when the only developed culture available seemed to be English culture. Nobody should be surprised if I felt the things I was saying were unprecedented, surprising and risky.

NO’G I don’t think you say anywhere in the book that the love poems are addressed to other men, even if it’s obvious to anyone who pays attention. Was it important to you to leave this unsaid?

CMacIB When the collection won a Saltire award, I heard that one committee member couldn’t believe his ears on being told it contained poems from one man to another. In his review for Chapman magazine, William Neill wrote that the poet was addressing his wife in the poem ‘In Rome’! Derick Thomson and I never talked about being homosexual, but I could sense he attached no importance to the fact; he was an exceptionally open and tolerant person. At the time when I was writing Uirsgeul / Myth, I taped the interviews with Edwin Morgan that helped him to “come out” in 1990. I made a detailed study of the coded lanague Morgan uses in his love poems. I think I found an excellent model there.

NO’G That leads me to a poem like ‘I climbed your sides in the half-dark night’ (‘The Scholar Looks Back’ 6) where the beloved’s hair is spoken of in rather different terms from, for example, the Poems to Eimhir…

CMacIB In the Poems to Eimhir, Sorley MacLean was able to evoke echoes from a very long tradition, from poets like Yeats and Blok, Shakespeare and Petrarch, Ovid and Propertius. It’s not so easy to do that when you are dealing with love between men. That may be why I borrowed material from Tsvetaeva, Mandelstam and Hölderlin in ‘Myth’.

But the topic you are handling is not all that important. Love remains love, whether you feel it for a man or for a woman. What matters is the prohibition, not being allowed to talk about it. Or it not having been allowed for centuries. That means you constantly have to struggle with dumbness, emerging from silence then disappearing into it again. Things have changed since I was a boy, and since the time when I wrote those poems. That took place incredibly fast, and it’s good that things have changed.

As regards landscape, I suspect we experience our mother’s body as a landscape when we are little infants, lying in the middle of it, or moving across it. That memory returns – at least, in my opinion – as adults with the body of someone we love, whether it belongs to a man or to a woman. I believe infants experience their mother’s body as something beyond gender, more all-embracing, broader than one single gender. That means you can compare either a man’s or a woman’s body to a landscape. It doesn’t make much difference.

NO’G Why don’t we talk for a bit about the form of the poems. You used long, unrhymed lines. Sometimes they are free verse, with a poem divided into paragraphs. At others, the metre is stricter, divided into stanzas. Were you following the example of other poets here?

CMacIB Look Niall, I taught myself Gaelic, far away from schools and courses. Until this very day I never obtained a certificate concerning my knowledge of the language, of grammar or idiom. When I discovered I could write in Gaelic, thoughts of metre and versification were far away. I was overwhelmed by the miracle of being able to say these things, to express them clearly, freely, without restraint. My interest in metre awakened long afterwards, when I left Edinburgh for Budapest. Maybe we can find another opportunity to talk about the poems I wrote then.

NO’G I would like to say something about the sequence which is at the heart of the book, ‘Myth’ itself. A love story runs through it, set in Scotland, in our own time. But you interweave further elements, from myth, from the lives of Russian poets. One poem is set in a Naples museum, while others are translated from Mandelstam and Hölderlin. What link do you see between these elements and the love story itself?

CMacIB When I chose the Gaelic title ‘Uirsgeul’, I intended it not as “novel”, but as “myth”. For me, the story in the sequence is about a man encountering a lover – in this case, another man. He discovers the lover is not human at all, but a god bearing the message that he may write poetry. That is what he does once the god has departed. The god also tells him there is no problem about him loving another man.

I took the way the titles of poems are presented – when there is a title – from the Préludes by Debussy, which I learned to play on the piano when I was at school. They appear between inverted commas, at the end of the poem, as if they were merely indications, or an after-thought.

The second part of your question is pretty complicated. Though my first degree was in English, I couldn’t identify with the culture associated with that language. That’s why I read a range of poets in different language, not in English translation, but in the original language, or in some cases, in Italian translation. I was strongly affected by Rilke, Baudelaire, Verlaine, Cavafy, Hofmannsthal and Pasolini. I also realised that Tsvetaeva was going to be particularly important for me. I also read A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle and To Circumjack Cencrastus by Hugh MacDiarmid. I observed in those books how words and lines from other poets can be interwoven with the lines you yourself are writing.

NO’G Would you say that you were a nationalist when you wrote these poems? I am thinking of poems like ‘Myth’ 8 (‘You gave me permission…’) or especially 11 (‘Sunrise over Glasgow’). Has your position changed since then?

CW I think when we talk about something like poetry, ‘nationalist’ is a label. Labels are not always appropriate. I prefer dealing with specific issues. From the time I was adolescent, I would have voted without hesitatin for an independent Scotland. For a Scottish Republic, without any sor of king or queen – with all respect for Sorley MacLean! But if we want to discuss culture, then perhaps I am an internationalist. Regarding metrics, for example. If you do detailed research into the characteristic metres of a specific language, it generally emerges that they have been borrowed from another language. Metre is a means of rendering language “other”, alien. In my opinion, it’s best for their to be an unceasing exchange between languages, for elements and qualities to be constantly shifting from one to the other, and coming back transformed.

NO’G It was Derick Thomson who published this book. How closely involved did he get with the poems? Or did he give you considerable freedom, leaving the responsibility entirely up to you? Did Thomson’s own poetry serve you as an example?

CMacIB The more time passes, the stronger and greater my respect, affection and gratitude to Derick Thomson become, even though dealing with him in the everyday wasn’t always easy. He was a sensitive, reserved and private person, frequently wounded and demeaned in the course of his life. I am not sure that Derick’s poetry had a great influence on me, except for showing me how to express ideas and images in the simplest manner possible. He did not get involved with my poems. Generally I did not receive any reference or reaction to the poems I put in the post to him. The latest issue of Gairm would arrive through the letter-box. Opening it, I would find my own poems published there. That was the most genuine and effective form of support he could possibly have offered.

Translated from the Gaelic: first published in Steall 1 (2016) pp. 26-28